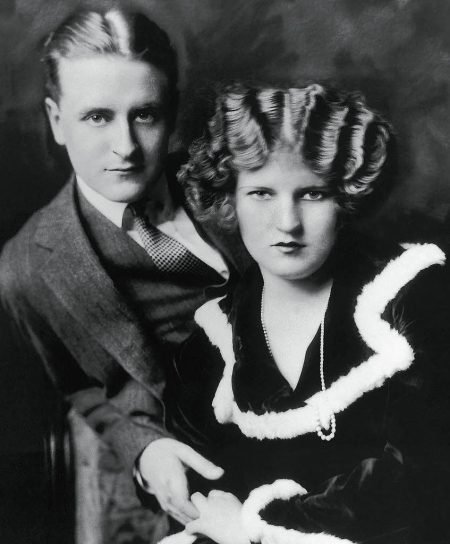

There has been a lot written about Zelda Fitzgerald in an effort to give her back her identity, and rightly so. She was the original wild child, in her words an “extravagant,” whose reckless inhibition made her a superstar. Even today, over a hundred years after her birth, her name, image, and legacy are so iconic that it is easy to forget how incredibly short was her reign, and how long was her downfall that left her wholly forgotten by the time of her death.

“Nothing could have survived our life.” Zelda

She was beautiful, witty, and a world class exhibitionist married to one of the great writers ever, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who based a substantial amount of his work on his observations of her. Their marriage was intense and toxic, and while he had a hand in her catastrophic decline, there can be little doubt that there was something in her that would have gone wrong even if he had never shown up. It would have just been a different kind of wrong.

“She probably thought terribly dangerous secret thoughts.” Sara Murphy

The teenage belle had an air of both well-bred gentility and a total of lack of concern for what others thought made her the object of scandal in hometown of Montgomery, Alabama. Several duels had already been fought over her when she met Scott Fitzgerald stationed nearby. He was a Princton dropout and an inept officer but he was sure of two things: he was going to be a world-famous writer and he was going to marry young madwoman in organdy ruffles who misbehaved under magnolia blossoms.

“Any girl who gets stewed in public, who frankly enjoys and tells shocking stories, who smokes constantly and makes the remark that she has ‘kissed thousands of men and intends to kiss thousands more’ cannot be considered beyond reproach. But I fell in love…and it is the beginning of everything.Zelda’s the only God I have left now.” Scott

When Scott’s first novel was a smash success, he carried her off to New York and married her. They were young, gorgeous, rich, and in love. Twenty year-old Zelda was the muse of the Jazz age; together they were Flaming Youth incarnate.

“This apparition, this double apparition, approached me. The two most beautiful people in the world were floating toward me, smiling. It was if they were angelic visitors.” Gilbert Seldes

Flamboyance was their specialty: running hand in hand down Fifty-seventh Street to jump fully clothed into a fountain, sliding down banisters at the Waldorf, dancing on tabletops, riding on the tops of taxis. Scott’s strategy was to egg her on to ever more outrageousness, then stand back and record the inevitable fireworks which he then turned into literary fodder. He would do this for years but by the time he realized how dangerous it was, it was too late to turn back.

“I couldn’t get mad at him and particularly not at Zelda; there was a golden innocence about them and they both were so hopelessly good looking.” Gilbert Seldes

He also began a lifelong habit of confiscating her journals and letters to use liberally in his novels and short stories. When she had a romance with a French aviator on the Riviera, he was shattered, but still managed to insert the incident into several works. When she set all of her clothes on fire after he flirted with an actress, it turned up in a variety of tellings.

“Everything that we have done is mine—if we make a trip—if I make a trip to Panama and you and I go around—I am the professional novelist and I am supporting you. That is all of my material. None of it is your material.” Scott

She accepted this as she accepted the fur coat, the Rolls Royce, the first-class trips to Europe, the Ritz but as Zelda wrote later, Nemesis was incubating. The fact that she was capable of anything meant that Scott was afraid to leave her alone and for the rest of his life his writing output suffered. He could not meet the demands of Zelda, without whom there would be no story, and his craft that demanded sustained periods of concentration.

“Without Zelda he might or might not have been a better caretaker of his genius; but it is folly to assign blame to either partner. They conspired in a dangerous game for which only they knew the rules.” Matthew Bruccoli

It couldn’t go on. Five years later they were still young but their gaiety now had the quality of a forced march. Now when they danced on table tops it was, as one onlooker said, with a resigned air of “this is what we do and now we will proceed to do it.” By then he was a drunk, a nasty, self-pitying one with a tendency to start brawls he couldn’t finish. As for Zelda, it was becoming clear even to those who loved her that something wasn’t right. One night after Scott paid too much attention to an aging Isadora Duncan, Zelda stood, threw herself over a table top and down a stone stairwell, head first. Other times she challenged Scott to join her in late night jumps off of a 30-foot cliff into rocky waters below.

“The aftermath of a Fitzgerald party was notoriously a painful experience.” Edmund Wilson

At 28, she took up the ballet. As her mental health degenerated her commitment to lessons took on an aspect of mania, rehearsing as much as ten hours a day, spinning in front of the giant glass that Scott called her whorehouse mirror. While she worked hard, training with a former colleague of Diaghilev, she had simply started far too late to master the art that she hope would save her, that “in dancing she would drive the devils that had driven her and achieve peace.” Her beloved teacher was eventually forced to tell Zelda that she would never be more than good, but by then Zelda was living in a mental hospital.

“You were constantly drunk. You didn’t work and you were dragged home at night by taxi-drivers when you came home at all. You said it was my fault for dancing all day. What was I to do?” Zelda

She laughed at things no one else could hear and believed that flowers were talking to her. She said she could smell ants. She grabbed the wheel of a car and tried to it off of a cliff because this was what the car wanted. A contemporary diagnosis was that of schizophrenia although a modern assessment is less certain.Perhaps today there would be treatment available that would have allowed her to live a full life but in the 1930s and ‘40s she suffered electroshock therapy, induced comas, and the good intentions of doctors who attempted to “reeducate” her into showing traditional wifely traits. There were several suicide attempts, occasional prison-like conditions, and possible sexual abuse from one of her doctors, which she turned to her advantage when blackmailing her way into a discharge.

“You were going crazy and calling it genius—I was going to ruin and calling it anything that came to hand. And I think everyone far enough away to see us outside of our glib presentation of ourselves guessed at your almost meglomaniacal selfishness and my insane indulgence in drink.” Scott

Scott was angry with her for attempting to use her own psychiatric experiences in her own writing of an autobiographical novel Save Me the Waltz;he had already appropriated them. Sections of her letters written during lonely and arduous hospital stays, and even from her doctors’ notes, would also show up in his work. He was even more furious that her illness put him squarely in her doctors’ cross hairs. At least one diagnosed a folie a deux. When they put it to him that his wife would never recover until he sobered up – something her family had long asserted – he wrote her carers long, defensive letters and continued to drink in defiance.

“Perhaps 50% of our friends and relatives would tell you in all honest conviction that my drinking drove Zelda insane – the other half would assure you that her insanity drove me to drink.” Scott

While he forbade her to write, when she became interested in painting he paid for her lessons. Throughout the rest of her life she would work, creating canvases in a style influenced by Van Gogh and Dali: modern, color-saturated, often distorted. Eventually Scott arranged for her to have an exhibition and press coverage in New York but when the reception focused on her troubled personal life rather than her talent, she had another breakdown and attempted suicide. She would rarely live outside of a hospital again.

“I think about Zelda. Those days when I was in love with a dazzling light—I thought she was a goddess. Triumphant, proud, fearless. Going at top speed in the gayest worlds we could find. She reached and took all the things life put before her until she collapsed and could reach no more. Now she’s a pathetic figure…Broken, humiliated, her radiant eyes with no luster, her fiery hair a frazzled mop. Sometimes her old spirit hovers about her, sometimes it’s on leave.” Scott

When Scott died in 1940, Zelda had been living for some years in Highland, a sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina. It boasted forward-thinking treatment along with beautiful grounds and a view of the nearby Blue Ridge Mountains. Eventually she recovered enough to live in Montgomery under her mother’s care. Now obsessed with religion, she threw herself into reading the Bible and writing tracts with a fervor she had once devoted to dance. She began a new novel – another attempt to retell and make sense of her history. Her painting continued but was a source of family friction when she refused all coercion to work in a more commercial style that would earn much needed money. Her mother frankly hated her work and made no secret of the fact that it frightened her.

Periodically, she returned to Highland for treatment and tune-ups. It was there in 1948 that she was sedated as she went to bed in preparation for an early morning shock treatment. While she was allowed to leave the grounds during the day, her room on the fifth floor was locked at night. A disgruntled employee started a fire in the hospital kitchen, Highland’s third arson in a year. The same woman delayed calling the fire department until it was too late for them to stop the blaze that rushed to the upper floors through a dumbwaiter. All that was found of Zelda under her charred remains was a single slipper.

“I must add another thing: this story is the fault of nobody but me. I believed I was a Salamander and it seems that I am nothing but an impediment.” Zelda

While her mother destroyed the bulk of her later paintings, enough of Zelda’s work existed elsewhere to allow – over 50 years later – several one-woman shows of her art. One was entitled appropriately, The Last Belle Standing.

Follow

Follow

June 25, 2014 at 11:47 pm

Excellent piece. I’ve visited the apartment here in L.A. that Scott was living in during his final days before moving in with Sheilah Graham and also walked over and saw Graham’s apartment (only about a block away) where he suffered his fatal heart attack. Not out of any morbid curiosity about the scene of his death but simply because I was interested to see where he was living when he was out here in California. I’m woefully ignorant when it comes to Zelda so your post filled in some gaps.